In the first days of the full-scale invasion, hundreds of Ukrainian researchers were heading westwards in crowded evacuation trains. At the Central Station in Warsaw they were met by their friends – researchers of the Polish Academy of Sciences. The Poles helped with housing, work, medical care.

We spoke with Jerzy Duszyński, the President of the Polish Academy of Sciences (we interviewed him in autumn last year) about the difficulties of the first, most complicated days of the war, about further plans to support Ukrainian researchers, as well as the Polish experience that Ukraine can use.

Professor Duszyński headed PAS from 2015 to 2022 and now continues coordinating the work on support and recovery of research in Ukraine.

We express our sincere gratitude to Jerzy Duszyński, a true friend of Ukraine, for this work!

– Mr. Duszyński, the Polish Academy of Sciences has been supporting Ukrainian researchers since the first days of the war. How did it all begin? How did the Academy make the first decisions about support?

– Warsaw Central Railway Station is just 100 meters away from the headquarters of the Polish Academy of Sciences. We can see it from our windows. So, when the war broke out, we went to the station, and we could see hundreds and hundreds of Ukrainian people with no idea where to go and what to do. Many of them were with small children. They were disoriented and extremely tired. There were volunteers giving them food and clothes.

Seeing that inspired our academy to work quickly with our institutes to host and support Ukrainian scholars displaced because of the war. We worked through our administrative channels to get that arranged by March 1.

– How did you manage to find the funds for this?

– At first we redirected some of our programs to support Ukrainian researchers. Very quickly we reached out to international organizations that we are a member of, and to partner academies with whom we have been working closely over the years. Very generous support has been provided by many of our partners. With the US National Academy of Sciences we have launched a number of calls for proposals. Additional funding has also been granted by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

– How many Ukrainians did the Polish Academy of Sciences support in the first days and how many today?

– From our resources, we supported 57 researchers from Ukraine in March 2022. With additional support, we have been able to offer funding for a total of 250 scientists, practically till the end of 2022.

– In which areas of Polish research do Ukrainian researchers most often work today? Which institutes opened their doors to them?

– These are two different questions. First, Ukrainian researchers currently work almost in all fields of research in Poland. The highest number of them are involved mainly in natural and technical sciences, but also social sciences is a popular field in this case.

In February 2022, when we launched our short-term program for researchers who flee the war, 50 out of 69 Institutes of PAS opened doors to scientists from Ukraine. Many institutes have hired scholars to their projects. Many of them organised ad hoc support to refugees.

– Recently, during the ‘Workshop on Rebuilding Research, Education, and Innovation in Ukraine’, you said that the Polish Academy of Sciences plans to support research groups from and in Ukraine. Please tell us a little more about this initiative. What kind of groups will these be, and what is the purpose of this particular form of support? What funds are planned to be allocated?

– The new program was launched on December 7, 2022. It will allow teams from Ukraine to do research under the supervision of experienced PIs who are citizens of Ukraine. Teams will be hosted at PAS Institutes for up to 3 years. During the project, all team members will hold a double affiliation.

The program is open for all research disciplines. However, preference will be given to teams undertaking activities in the fields of mathematics, computer sciences and engineering, telecommunications, energy and environmental engineering, material sciences, agriculture, physics, chemistry, life sciences and biomedical sciences.

The maximum budget for a project under this program is up to 900.000 PLN (approx. $200,000 USD) per year for up to three years, in total up to 2,700,000 PLN (approx. 600,000 USD).

Initial contracts will be valid for 12 months with a possibility of extension, subject to satisfactory review of progress reports and contingent upon funding availability.

– During your visit to Ukraine, you said that you dream of establishing a virtual Ukrainian institute with a global network. What kind of institute is this and have you managed to take the first steps toward realizing this dream?

– I would be happy if in Poland we could set up a network of research groups led by principal investigators (PIs) originating from Ukraine and having contacts with selected research institutions in Ukraine. Such PIs could present their scientific achievements (publications or congress speeches) with two affiliations – of a PAS Institute in which the team is functioning and the Ukrainian institution. The team, and we are talking about a total of 5 people, will also hold double affiliation. Moreover, some of them could work from Ukraine, which will give a chance to those who do not want to or cannot leave the country to be involved in the project. Together with the US Academy of Sciences, we have recently announced a call (Long Term Program, LTP) under which we will generously fund the research of such teams for up to 3 years.

At the end of December 2022, after two four-year terms, I am ending my presidency of the PAS. However, I have been entrusted by the PAS president-elect to continue with support and recovery of science in Ukraine.

In this regard, I would like to bring the teams established under the LTP in 2023 into contact with each other and be centrally supported by some form of mentoring. For instance, a virtual Ukrainian institute might be created. If other countries where many Ukrainian scholars operate followed this path, we could think about a global Virtual Ukrainian Institute.

Currently, the world research community is supporting scholars from Ukraine in further internationalization. In the future, these people could be a backbone of a new Ukrainian science and research sector. My dream is that this type of virtual research institution would be supported and would reach the critical mass needed for the future recovery of science in Ukraine.

– Poland fundamentally rebuilt the structure of higher education and research after joining the EU. In your opinion, what experience of this restructuring would be useful for Ukraine? Conversely, what mistakes (which were made in Poland) should be avoided in Ukraine today, during the war, and during the post-war recovery?

– My main advice is to focus on human capital. A prolonged war could lead to degradation of the human capital of Ukraine’s research and higher education. It will be more difficult to recover the capital. Without appropriate countermeasures, there may be a significant generation gap in Ukrainian research institutions, combined with a huge brain drain.

In addition, practicing science, especially experimental science, in Ukraine has been underfunded for many years and is now facing extreme difficulties.

Not surprisingly, many talented researchers are either trying to get a foreign affiliation or are quitting. How can the problem be solved?

Certain actions come to my mind. First, it is injecting funds into selected scientific units in Ukraine, especially those operating away from the front line. We have to keep in mind that russian missiles have a long range. Human capital is harder to hit with rockets and less vulnerable to energy cuts than large research infrastructure. Give a few selected scientific institutions in Ukraine the means to speed up their development. External funds would flow to these institutions, which would accept international oversight of their spendings. International supervisory boards, composed of prominent representatives of science and innovation, are now a standard practice at the leading scientific institutions. This is the optimal way to ensure proper development and trust.

It is also a chance to break with nepotism, corruption and low representation of women in leadership bodies which in Ukraine, unfortunately, also in some research and higher education units have reached a systemic level.

We should not forget about foreign research institution which host Ukrainian scholars. Maybe it is a less obvious way of support, but assistance to foreign institutions of science and higher education organizing support for Ukrainian researchers who have found themselves outside Ukraine because of the war is important. Actually, these places are secure spots to preserve constant access to science activities for many Ukrainian researchers. Nevertheless, these institutions should not contribute to brain drain, but rather strengthen the human capital of science in Ukraine.

For this to happen, researchers from Ukraine should maintain a close connection with the chosen scientific institution or university in Ukraine. In addition to the affiliation of the institutions hosting them outside Ukraine, they should also maintain the affiliation of the selected institution in Ukraine. As will be the case in the research groups established under the LTP program. It’s also a task for Ukrainian institutions to keep their affiliation. We heard that contracts of scholars who left were terminated. International mobility in science is a typical way of gaining experience, even when a researcher is planning to leave for a semester or an academic year. I would call universities to be more flexible in this case.

– During the ‘Workshop on Rebuilding Research, Education, and Innovation in Ukraine’ academician Yatskiv and other researchers said that the Polish experience is an example of how the NAS of Ukraine should be reformed. How did the transition from the essentially post-Soviet system take place in Poland? What would you advise our researchers?

– Scientific personnel is not built from the scratch overnight. It’s a process for years, decades or even generations. However, the rules of the functioning of researchers can be changed quite quickly. For instance, it is known what is unacceptable. Lack of transparency, corruption, plagiarism, nepotism. We had all of this, too. Our problem was also multi-tenure, the employment in many scientific institutions, sham employment, etc. This was banned overnight in Poland by the law in 2010.

Let us take transparency. It is now fostered by considerable digitization of science. We have the possibility to check the achievements of a scientist in large bibliometric databases, such as SCOPUS. Of course, there are fields in which publications could be in the native language. But there are relatively few of them. Researchers in majority of fields, with no doubt, should publish papers in international journals of the highest possible reputation. Only the research results presented in such journals should be a basis for further career development.

– Over the past nine months, the world has changed and continues to change rapidly. The world security system is being rethought, and the priorities of research are changing. What changes are noticeable in the Polish Academy of Sciences and Polish science?

– The war in Ukraine proved more than ever how much we depend on international cooperation in science. It is thanks to our international partners that we can continue supporting Ukrainian scholars.

Luckily, we are not a military institution and priorities for many Institutes of the PAS, remain the same, and this is doing science, the best science.

– What is the ratio of basic and grant (competitive) funding in Poland?

– It depends on the institution and its staff abilities in applying for grants and attracting additional (donors’) funding. For instance, in the PAS as a whole we have two sources of funding – budgetary, which is state funding, and non-budgetary, these are grants, donations, etc. This ratio obviously varies depending on the institute. Our best institutes get most of financial support from grants.

– One of the most problematic aspects of Ukrainian research is implementation of innovations and developments into industrial production. And how is this problem solved in Poland? How are inventions implemented and commercialized? How would you rate the relationship between science and business in Poland? This is a problem for Ukraine. And what should be done to make it truly successful?

– This is also our problem. It takes both good science and innovative industry to apply scientific achievements to the industry. It takes two to tango. Meanwhile, in Poland, science usually dances solo.

There are huge institutions in the world, both state and commercial, focused on developing and implementing innovations. It is difficult for an entity with limited human and financial resources to compete with them. From the point of view of a state that is aware of its limitations, the way out seems to be to focus on certain research priorities.

But enlisting such priorities is met with reluctance by specialists working in disciplines not covered by these priorities. And this is the vast majority of the scientific staff. In Poland, when they started thinking about priorities in the European Commission’s Smart Specializations Platform, they ended up watering down the program so much that in the end no specific priorities were singled out. This is a difficult issue. But I think Ukraine should try to set its priorities.

– How are contacts made in the PAN with the government? Is it important to have a lobby in the government, in the parliament? How can one advocate researchers’ interests?

– Let me use an example. When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, the expert voice of our Academy was very strong. We issued dozens of positions and studies published and discussed in major national press titles and commented on in large numbers on social media. They reached the public. However, no one from government circles addressed us to elaborate on an issue or comment on the official solutions adopted.

This is sad, but it shows the state of affairs. So, in this regard, it is difficult for me to advise since we have not been able to make such contacts ourselves.

– Professor Duszyński, you have repeatedly said that Ukrainian research support is a priority of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Why is this important to you?

– Why it is important? I have had contacts with representatives of science in Ukraine for years. I have many good colleagues in Kyiv, Lviv or Ivano-Frankivsk. I feel competent in this subject. I know the strengths and weaknesses of the system of science in Ukraine because we either had them or still have them in Poland.

While the cruel and devastating war is going on I am wholeheartedly committed to programs to support scientists in Ukraine. I believe it is the Polish ‘raison d’etat’ to support Ukraine struggling against the aggression of the russian federation.

I believe that the heroic struggle of Ukrainians for their own state will be successful sooner or later. Ukraine will become a member of the family of democratic states and with the help of these states will rebuild itself. We are convinced that the rationality of the decisions made by chief stakeholders and their acceptance by society are important for the prosperity of the country.

And places to forge the elite that will guide the reconstruction of Ukraine are research institutions and universities.

I am also aware that a great responsibility rests on the shoulders of Ukrainian scholars when it comes to building their own independent and democratic state. There is a growing trend toward nationalist ideology in the russian federation. It is amplified by aggressive and deceitful state propaganda. Ukrainian society must resist and react to disinformation and russian lies with rationality and honesty.

Institutions of science and higher education should play an important role in building a democratic state. This is an equally important task to be combined with participating in the global progress of science and technology and building a modern economy based on advanced technologies.

– You have been a true friend and supporter of the NRFU. What advice would you give the Foundation on building its development strategies in the short-term and long-term perspectives?

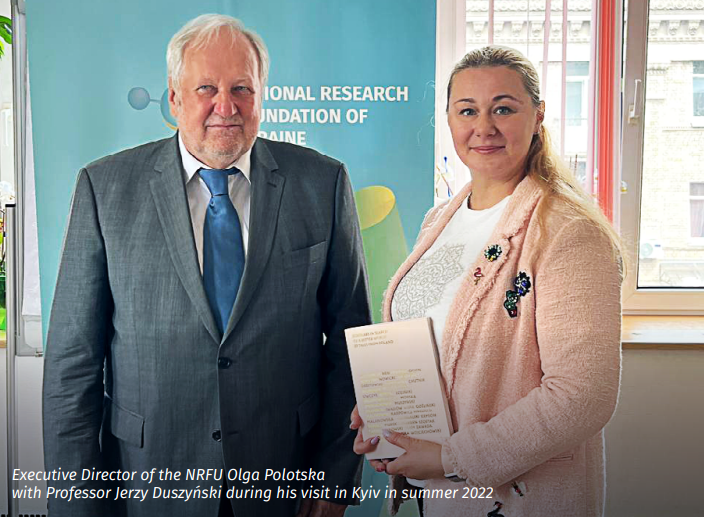

– We have met several times in Kyiv in your office. Most recently in July 2022. Each time I came out of my conversations with you with positive feelings. You are doing a fantastic job! Focus on the success that you unquestionably have. There are also decisions that are not right about funding certain projects, but we learn from mistakes. Learn how to avoid this in the future, but don’t spend too much effort to resolve these misguided decisions.

Go forward, support and identify the researchers who will be the future of science in Ukraine. That is what you should focus on, and in these efforts, I wish you all the best!

Interviewed by Svitlana GALATA